What I learned building a VM in Zig (badly)

by Rui Carrilho

I spent the last two weeks or so building a VM, following Justin Meiners brilliant article on it. Keep that article in hand. What started as a seemingly simple educative project ended up with me tearing my hair out while Claude, DeepSeek (pre-R1) and ChatGPT failed to help me through an ultimately very simple sign extension problem.

I now share with you my journey, in the hope that we can commiserate on my massive skill issue, and that you can avoid such problems if you run into them in the future.

I must however manage your expectations - despite my doing a PhD in Computer Science, my background was not in this area until recently. I (sadly) bypassed many important stuff such as PC architecture, compilers and (very sadly) data structures. I am learning all of that on my own, and if in the following stuff you see the noobness showing, well, now you know why.

All code available at my github repo.

So without further ado, let’s dive in.

VMs

I will not stay long in this section. Others far more brilliant than me can explain what a VM is supposed to be. To put it short, you’re basically simulation a whole other (weaker) PC within your PC. At this point, though the authors never mention it, it would be a good idea for you to have at least an inkling of how a computer works, and for that, you should probably know some Assembly. No need to be fluent at it, just know what sorts of OPs it performs, how they roughly work.

You should also understand how a computer architecture works. At the end of the day, all a computer does is math, look at certain places in memory, fetch info from those bits, do math on them, place them on other bits, and so on. There are many different architectures (ways a PC can do these OPs in), and we’re working with the LC-3 architecture. It’s nice and simple to let us get started while still having some depth so we can see the full range of how computers work.

Memory

Know what memory is? It’s basically where the computer stores whatever data it’s using/gonna be using/has used. Declaring it in Zig is easy enough:

const MEMORY_MAX = 1 << 16;

var memory: [MEMORY_MAX]u16 = undefined;

Zig’s neat little const means that we don’t have to specify the type, the compiler itself will decide the best type for MEMORY_MAX (in this case a u16, as most types in this). We then initialize an array of that size to represent our memory. Child’s play!

Registers

Here is where I decided to start being too smart for my own good. I really wanted to see how Zig’s imports worked, so I put the registers in a different file, like so:

pub const Register = enum(usize) {

R_R0 = 0,

R_R1,

R_R2,

R_R3,

R_R4,

R_R5,

R_R6,

R_R7,

R_PC, // program counter

R_COND,

R_COUNT,

};

pub var reg: [@intFromEnum(Register.R_COUNT)]u16 = undefined;

And I imported it like:

const registers = @import("registers.zig");

const Register = registers.Register;

const reg = registers.reg;

From then on I had to refer to every individual register like Register.R_COND or Register.R_PC. Too wordy. That’s the price I pay for not just declaring these in main.zig and being done with it.

Instructions

We then gotta get our instruction set going. Instruction are commands which tell CPUs what to do. Each have a code that specifies what the instruction does, and this code is called an opcode. Different architectures have different amounts of opcodes, and LC-3 has 16 of them. I also decided to be smart and define them in their own file like so:

pub const OpCode = enum(u8) {

BR = 0x0, // branch

ADD = 0x1, // add

LD = 0x2, // load

ST = 0x3, // store

JSR = 0x4, // jump register

AND = 0x5, // bitwise and

LDR = 0x6, // load register

STR = 0x7, // store register

RTI = 0x8, // unused

NOT = 0x9, // bitwise not

LDI = 0xA, // load indirect

STI = 0xB, // store indirect

JMP = 0xC, // jump

RES = 0xD, // reserved (unused)

LEA = 0xE, // load effective address

TRAP = 0xF, // execute trap

};

…with the same wordiness associated with calling them up. Luckily this time it’s more readable.

Flags

After this came the condition flags, which are meant to be put on your Register.R_COND, to help it to branch OPs. Implemented like:

pub const Flags = enum(u8) {

FL_POS = 1 << 0, // P

FL_ZRO = 1 << 1, // Z

FL_NEG = 1 << 2, // N

};

Also imported too verbosely.

The main loop

Now let’s see. Our VM is supposed to do this:

1 - Load an instruction from memory at the registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] (yes, Zig was not ok with receiving an enum instead of an int while accessing registers.reg, so I had to wrap it in @intFromEnum… for all cases;

2 - Increment Register.R_PC: easy enough, registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] += 1;

3 - Check the opcode of the instruction: const op = instr >> 12; (by using the right-wise bit shift we can get the “first” 4 bits of the 16 bit instruction) followed by a switch statement

4 - Perform the op, depending on which it is, according to the parameters for LC-3

5 - Return to 1, repeat until break

Now is the part where I would show you the full code, but tbh, I did a lot of changes to the main loop attempting to debug it, and I’m proud of the debugging mess, so rather than mess it up to show you, I’d rather just gloss over this part. The snippets I’ve shown you are enough, now let’s look at each op.

Actually, before that…

Our VM doesn’t work in a vacuum. A PC doesn’t ever really stand there, it’s always doing something. In this case, we need to pass a VM image for the pretend PC to run. Let’s get that code out of the way and showcase how Zig handles outside arguments while we’re at it:

const args = try std.process.argsAlloc(std.heap.page_allocator);

defer std.process.argsFree(std.heap.page_allocator, args);

if (args.len < 2) {

std.debug.print("lc3 [image-file1] ...\n", .{});

return;

}

for (args[1..]) |arg| {

readImage(arg) catch |err| {

std.debug.print("Failed to read image: {}\n", .{err});

return;

};

}

Disregard the readImage helper for now. Using std.process.argsAlloc(std.heap.page_allocator) we can get the args given to the command line (with the -- separator), and if the len matches what we want, we then call readImage and we’re off to the races.

The OPs

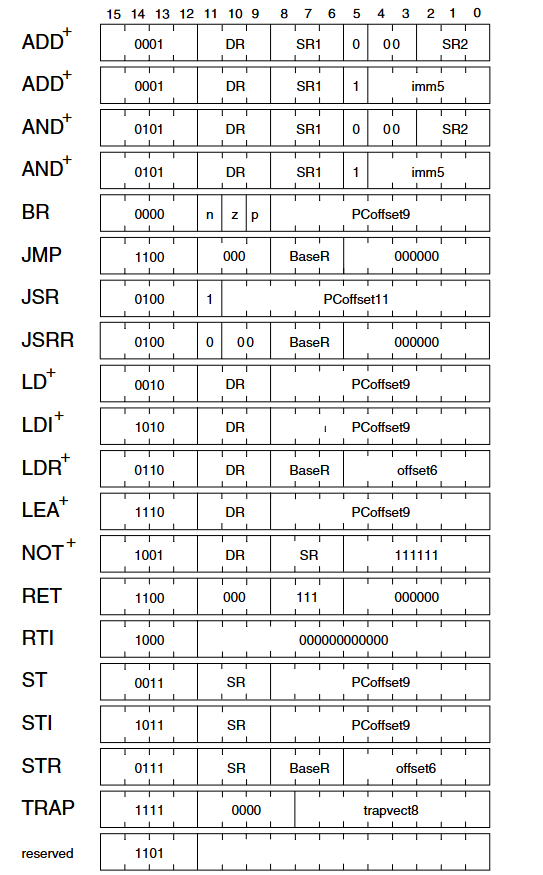

Now we get to the ops. For this, we need the LC-3 ISA appendix document, which specifies how each op is meant to be handled:

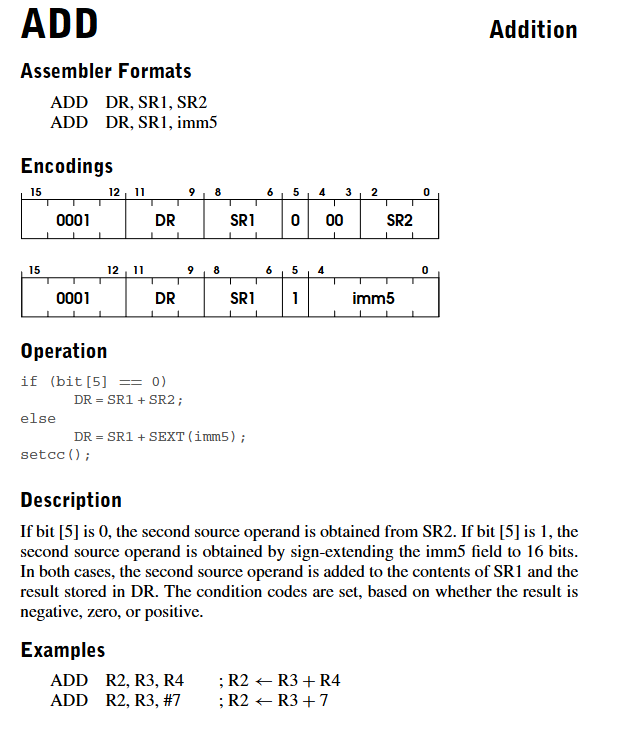

The image above is what each instruction is supposed to look like. This first four bits (which we get with the right-wise shifting) say which op is gonna be done, the next bits give the necessary data for the it. Each op gets specified in the documentation like so:

That’s the ADD op. The first four bits (0001) are the op type, the next 3 bits are the Destination Register (the register where you will store the result), the 3 bits after that are Source Register 1 (the first register from which we will take the number to add), and after that, it varies. If the bit immediately after SR1 is 0, the number to add will be two 0 bits afterward in Source Register 2. If not, it’ll be in the next 5 bits, the “immediate value”, which need to be sign extended. Let’s talk about that.

Sign extension

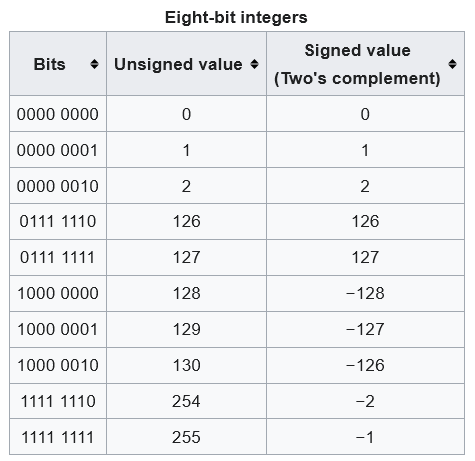

See, the immediate value is only 5 bits in length, but the Registers are u16s, so we need to turn the 5-bit integer into a u16 before we proceed. Now let’s think about this. If it’s a positive number, we just need to fill it up from the left with zeros. But it it’s a negative, we need to do this using Two’s Complement. Here’s an image representing the idea:

If you try to take a negative number and just put more 0s to the left, you will wind up with the wrong numbers. If the first bit is 1, that means the number is negative, and you need to pad it out with 1s instead. The following Zig code implements this:

fn signExtend(x: u16, bit_count: u16) u16 {

if (((x >> @intCast(bit_count - 1)) & 1) == 1) {

// If sign bit is set, fill all higher bits with 1s

return x | (@as(u16, 0xFFFF) << @intCast(bit_count));

}

return x;

}

Not much Zig to show here, other than the @as built-in, which converts the 1111111111111111 from hex into a u16. We then perform an OR binary operation to fill up every other bit to the left with 1s. Easy enough. But there will be complications from this later.

Without further ado, let’s get to the ops!

Actually, we need one more thing first…

Ok, there’s one final bit we need. Remember the condition flags we set up earlier? The LC-3 needs those to see whether a number is negative, positive, or a zero whenever we update a register. We do that with this code:

fn updateFlags(r: u16) void {

if (registers.reg[r] == 0) {

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_COND)] = @intFromEnum(FL.FL_ZRO);

} else if ((registers.reg[r] >> 15) == 1) { // Check leftmost bit for negative

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_COND)] = @intFromEnum(FL.FL_NEG);

} else {

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_COND)] = @intFromEnum(FL.FL_POS);

}

}

Adn that’s that for helper functions (for now)! Let’s get to the ops!

The ADD op

Now that we have sign extension out of the way, we can implement the ADD op. Here it is in Zig:

switch (op) {

@intFromEnum(OP.ADD) => {

// Destination register (DR)

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

// First operand (SR1)

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

// Whether we are in immediate mode

const imm_flag = (instr >> 5) & 0x1;

if (imm_flag == 1) {

const imm5 = signExtend(instr & 0x1F, 5);

registers.reg[r0] = registers.reg[r1] +% imm5;

} else {

const r2 = instr & 0x7;

registers.reg[r0] = registers.reg[r1] +% registers.reg[r2];

}

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

...

Rather simple. We use rightwise shift operations to see what’s on each bit, put them in the right registers, then do the adding, and put the result in the right register. But you will notice there is a trick to the additions that’s quite necessary to get this working in Zig.

We perform wrapping addition (+%) instead of a normal one, as performed in the Meiners article. The reason for this is simple, but took me hours worth of debugging - see, when we perform sign extension, since our types are u16, we don’t really get negative values, we get enormous positive ones, close to the limit of 65536 (2^16). As such, when we add sign extended integers to the ones in the register, we get integer overflows. I learned this with help from friends - in C, integer overflows are defined behavior; the result wraps around modulo (UINT16_MAX + 1) automatically, and it gets to where it would be if a negative integer had been provided instead. But in Zig, the compiler instead panics, and the program crashes. To get the behavior we want, we must specify the operation as wrapping addition with +% instead.

And it then proceeds as normal. We call updateFlags at the end, and call it a day for the op.

Now we gotta do the rest. I’ll put the code here, but feel free to do them yourself if the mood strikes you.

The LDI op

LDI means “load indirect” - loads a value from a location in memory into a register. There are details on how this works, but Meiners explains it extremely well in his article, you can read it there. The code is as follows:

@intFromEnum(OP.LDI) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

const effective_addr = memRead(registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] +% pc_offset);

registers.reg[r0] = memRead(effective_addr);

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

Disregard the break, it’s a stupid remainder from debugging, which I refuse to remove for foolish pride. The memRead will also be explained later.

AND

I will simply start pasting the code from this point on:

@intFromEnum(OP.AND) => {

// AND

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

const imm_flag = (instr >> 5) & 0x1;

if (imm_flag == 1) {

const imm5 = signExtend(instr & 0x1F, 5);

registers.reg[r0] = registers.reg[r1] & imm5;

} else {

const r2 = instr & 0x7;

registers.reg[r0] = registers.reg[r1] & registers.reg[r2];

}

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

NOT

@intFromEnum(OP.NOT) => {

// NOT

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

registers.reg[r0] = ~registers.reg[r1];

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

BRANCH

@intFromEnum(OP.BR) => {

//std.debug.print("calling branch op here\n", .{});

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

const cond_flag = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const cond = (cond_flag & registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_COND)]);

//std.debug.print("BR: cond_flag={}, pc_offset={}, cond={}, current_PC={X:0>4}\n", .{ cond_flag, pc_offset, cond, registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] });

if (cond > 0) {

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] +%= pc_offset;

//std.debug.print("Branch taken, new PC={X:0>4}\n", .{registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)]});

}

//break;

},

I refuse to remove the slightest bit of debugging comments. Bask in my skill issue.

JMP

@intFromEnum(OP.JMP) => {

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

if (r1 == 0x7) {

std.debug.print("registers.reg[r1]: {}\n", .{registers.reg[r1]});

}

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] = registers.reg[r1];

//break;

},

JSR

@intFromEnum(OP.JSR) => {

const long_flag = (instr >> 11) & 1;

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R7)] = registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)];

if (long_flag != 0) {

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x7FF, 11);

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] +%= pc_offset;

} else {

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] = registers.reg[r1];

}

//break;

},

LD

@intFromEnum(OP.LD) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

registers.reg[r0] = memRead(registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] +% pc_offset);

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

LDR

@intFromEnum(OP.LDR) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

const offset = signExtend(instr & 0x3F, 6);

registers.reg[r0] = memRead(registers.reg[r1] + offset);

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

LEA

@intFromEnum(OP.LEA) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

registers.reg[r0] = registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] + pc_offset;

updateFlags(r0);

//break;

},

ST

@intFromEnum(OP.ST) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

try memWrite(registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] +% pc_offset, registers.reg[r0]);

//break;

},

STI

@intFromEnum(OP.STI) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const pc_offset = signExtend(instr & 0x1FF, 9);

const effective_addr = memRead(registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] + pc_offset);

try memWrite(effective_addr, registers.reg[r0]);

//break;

},

STR

@intFromEnum(OP.STR) => {

const r0 = (instr >> 9) & 0x7;

const r1 = (instr >> 6) & 0x7;

const offset = signExtend(instr & 0x3F, 6);

//std.debug.print("registers.reg[r1]: {},\noffset: {},\ninstr: {},\ninstr & 0x3F: {},\nregisters.reg[r0]: {}\n", .{ registers.reg[r1], offset, instr, instr & 0x3F, registers.reg[r0] });

try memWrite(registers.reg[r1] +% offset, registers.reg[r0]);

//break;

},

Trap routines

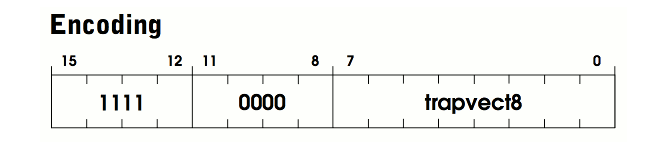

Now we get to the trap routines. These are how we get and process input from the user. We treat them as ops, namely OP.TRAP, and they involve a switch case of their own, inside that op. This is how they look:

The trapvect8 you see specifies the specific routine that is supposed to be run. I chose to specify them in their own file like so:

pub const TrapCodes = enum (u8) {

GETC = 0x20, // get character from keyboard, not echoed onto the terminal

OUT = 0x21, // output a character

PUTS = 0x22, // output a word string

IN = 0x23, // get character from keyboard, echoed onto the terminal

PUTSP = 0x24, // output a byte string

HALT = 0x25, // halt the program

};

Meiners has a cool little bit where he explains how this thing works in the real LC-3, check it out. In either case, I will now show the code for each trap op.

GETC

switch (trap_vector) {

trap.GETC => {

std.debug.print("GETC trap called\n", .{});

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)] = try std.io.getStdIn().reader().readByte();

std.debug.print("Got byte: {}, PC before: {X:0>4}, R7: {X:0>4}\n", .{ registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)], registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)], registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R7)] });

updateFlags(@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0));

//registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)] = registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R7)];

//std.debug.print("PC after: {X:0>4}\n", .{registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_PC)]});

},

Once more, please ignore the debugging, it was caused by skill issue.

OUT

trap.OUT => {

const output: u8 = @truncate(registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)]);

std.debug.print("{c}", .{output});

//try std.io.getStdOut().writer().writeAll("\n");

},

PUTS

This one is used in the example by Meiners. All I’d say here is that there’s no need to bother with the fflush equivalent in Zig - just use std.debug.print to print it to the console and be done with it.

trap.PUTS => {

var addr: u16 = registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)];

while (memory[addr] != 0) : (addr += 1) {

const char: u8 = @truncate(memory[addr]);

std.debug.print("{c}", .{char});

}

//try std.io.getStdOut().writer().writeAll("\n");

},

IN

trap.IN => {

std.debug.print("Type your character: ", .{});

const char = try std.io.getStdIn().reader().readByte();

std.debug.print("character: {c}", .{char});

//try std.io.getStdOut().writer().writeAll("\n");

registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)] = char;

updateFlags(@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0));

},

PUTSP

trap.PUTSP => {

var addr: u16 = registers.reg[@intFromEnum(Register.R_R0)];

while (memory[addr] != 0) : (addr += 1) {

const first_part: u8 = @truncate(memory[addr] & 0xFF);

std.debug.print("{c}", .{first_part});

const second_part: u8 = @truncate(memory[addr] >> 8);

if (second_part != 0) {

std.debug.print("{c}", .{second_part});

}

}

//try std.io.getStdOut().writer().writeAll("\n");

},

HALT

trap.HALT => {

std.debug.print("HALTING\n", .{});

//try std.io.getStdOut().writer().writeAll("\n");

running = false;

},

And that’s all when it comes to ops.

Reading the image files

All this above pertained to the operations our VM does. But how exactly does it acquire the data it does those operations on? From an image file, of course! So now we have to give our VM the ability to read those. It all starts with this code:

pub fn readImageFile(file: std.fs.File) !void {

// Read the origin value

var origin: u16 = undefined;

const origin_bytes = try file.read(std.mem.asBytes(&origin));

if (origin_bytes != @sizeOf(u16)) return error.InvalidRead;

// Swap to correct endianness

origin = swap16(origin);

//on second thought, maybe this is unnecessary in this implementation, since we don't really use fread

// Calculate maximum number of u16 values we can read

//const max_read = MEMORY_MAX - origin;

// Read directly into memory slice starting at origin

var dest_slice = memory[origin..];

const items_read = try file.read(std.mem.sliceAsBytes(dest_slice));

const words_read = items_read / @sizeOf(u16);

// Swap endianness for each read word

var i: usize = 0;

while (i < words_read) : (i += 1) {

dest_slice[i] = @byteSwap(dest_slice[i]);

}

}

We gotta remember that fread doesn’t quite work the same here, so we use file.read(std.mem.asBytes(&origin instead)) instead. The whole bit with MEMORY_MAX can also be avoided. swap16 could probably be done with a built-in (and it was in fact done with the @byteSwap built-in when the other implementation gave me weird problems), but I chose to follow the author’s guide and implement it as such:

fn swap16(x: u16) u16 {

return (x << 8) | (x >> 8);

}

Nothing to it. This is to make sure we swap to little endian, as LC-3 programs are big-endian. You can check that endianness out yourself, this article is getting too long as is, sorry.

We also define this readImage helper to take a string as input and turn it into a file (there’s probably a more elegant way to do this in Zig, but alas, I suffer from skill issue):

fn readImage(image_path: []const u8) !void {

const file = try std.fs.cwd().openFile(image_path, .{});

//std.debug.print("successfully read file {}", .{file});

defer file.close();

try readImageFile(file);

}

Memory mapped registers

These are some special registers that can’t normally be accessed from the register table, and to work with them, you need to read and write to the memory location. I implemented them in another file (yeah, I know, this one was completely unnecessary and probably yielded no real advantage):

pub const MemoryRegisters = enum (u16) {

MR_KBSR = 0xFE00, //keyboard status

MR_KBDR = 0xFE02 //keyboard data

};

Now we can finally do the functions to read from and write to memory. We write with memWrite, which is easy as pie:

fn memWrite(address: u16, val: u16) !void {

memory[address] = val;

}

And read with memRead, which is a bit harder, because we have to consider the memory mapped registers:

fn memRead(address: u16) u16 {

if (address == @intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)) {

if (checkKey()) {

memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)] = (1 << 15);

// Read a single character

const stdin = std.io.getStdIn();

if (stdin.reader().readByte()) |char| {

memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBDR)] = char;

} else |_| {

memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)] = 0;

}

} else {

memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)] = 0;

}

return memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)];

} else if (address == @intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBDR)) {

// Clear the ready flag after reading KBDR

memory[@intFromEnum(MR.MR_KBSR)] = 0;

}

return memory[address];

}

And that’s the last VM-sensitive code of the bunch. But there’s still a bit more groundwork to cover before this is ready to go.

The remaining groundwork

The following has absolutely nothing to do with VMs, but was necessary to get this thing working. Since the code Meiners used used internal C libraries, I had to jump through some hoops to get this working here. Managed to learn how to import and use C libraries, and how to use external functions as well. Without further ado, I just dump the code:

var hStdin: ?HANDLE = INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

var fdwOldMode: DWORD = undefined;

var fdwMode: DWORD = undefined;

//for signal handling

const c = @cImport({

@cInclude("signal.h");

});

//signal handler type

const SignalHandler = fn (c_int) callconv(.C) void;

//signal handler

export fn handleInterrupt(sig: c_int) callconv(.C) void {

restoreInputBuffering() catch |err| {

// Handle the error

std.debug.print("Failed to restore input buffering: {}\n", .{err});

};

std.debug.print("\n", .{});

std.process.exit(@intCast(sig));

}

// Add this with your other extern declarations

pub extern "kernel32" fn ReadConsoleInputA(

hConsoleInput: windows.HANDLE,

lpBuffer: [*]INPUT_RECORD,

nLength: windows.DWORD,

lpNumberOfEventsRead: *windows.DWORD,

) callconv(windows.WINAPI) windows.BOOL;

// to set up signal handling

fn setupSignalHandler() void {

//std.debug.print("trying to get a signal here", .{});

_ = c.signal(c.SIGINT, handleInterrupt);

//std.debug.print("launched the function", .{});

}

Aaaaaand groundwork to the groundwork added here:

//Windows specific stuff declared here

const windows = std.os.windows;

const HANDLE = windows.HANDLE;

const DWORD = windows.DWORD;

const INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE = windows.INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

const kernel32 = windows.kernel32;

//courtesy of Claude, solving an error

const INPUT_RECORD = extern struct {

EventType: windows.WORD,

Event: extern union {

KeyEvent: KEY_EVENT_RECORD,

MouseEvent: MOUSE_EVENT_RECORD,

WindowBufferSizeEvent: WINDOW_BUFFER_SIZE_RECORD,

MenuEvent: MENU_EVENT_RECORD,

FocusEvent: FOCUS_EVENT_RECORD,

},

};

const KEY_EVENT_RECORD = extern struct {

bKeyDown: windows.BOOL,

wRepeatCount: windows.WORD,

wVirtualKeyCode: windows.WORD,

wVirtualScanCode: windows.WORD,

UnicodeChar: windows.WCHAR,

dwControlKeyState: DWORD,

};

// You'll need these structs if you plan to handle other event types

const MOUSE_EVENT_RECORD = extern struct {

// Add fields as needed

};

const WINDOW_BUFFER_SIZE_RECORD = extern struct {

// Add fields as needed

};

const MENU_EVENT_RECORD = extern struct {

// Add fields as needed

};

const FOCUS_EVENT_RECORD = extern struct {

// Add fields as needed

};

pub extern "kernel32" fn GetNumberOfConsoleInputEvents(

hConsoleInput: windows.HANDLE,

lpcNumberOfEvents: *windows.DWORD,

) callconv(windows.WINAPI) windows.BOOL;

pub extern "kernel32" fn PeekConsoleInputA(

hConsoleInput: windows.HANDLE,

lpBuffer: [*]INPUT_RECORD,

nLength: windows.DWORD,

lpNumberOfEventsRead: *windows.DWORD,

) callconv(windows.WINAPI) windows.BOOL;

// Import Windows API functions that aren't in the standard bindings

pub extern "kernel32" fn FlushConsoleInputBuffer(hConsoleInput: windows.HANDLE) callconv(windows.WINAPI) windows.BOOL;

const ENABLE_ECHO_INPUT = 0x0004;

const ENABLE_LINE_INPUT = 0x0002;

There isn’t all that much to explain, and as you can tell if you read the comments attentively enough, I had help from Claude in the most boring bits, so I won’t pretend to lecture you about this.

We’re done!

You can now simply get the VM images for the games you want to run (here’s 2048 and Rogue), and run zig run -lc src\main.zig -- src\2048.obj, or whatever the path to your VM is.

And there you go! If you followed the guide till here, it should be working. I advise you to read the rest of Meiners’ article, it has a nice little alternative method of doing this with much less code. I chose not to adapt that to Zig, for reasons of laziness.

In any case, you now have a functioning Zig LC-3 VM. Hopefully you’ll have learned something. I know I did!

Till the next one, dear reader. I have some ideas for stuff to do next…